Contemporary

accounts of the plague are often varied or imprecise. The most commonly noted

symptom was the appearance of buboes (or gavocciolos) in the groin, the neck

and armpits, which oozed pus and bled when opened. Boccaccio's description is

graphic:

Contemporary

accounts of the plague are often varied or imprecise. The most commonly noted

symptom was the appearance of buboes (or gavocciolos) in the groin, the neck

and armpits, which oozed pus and bled when opened. Boccaccio's description is

graphic:

"In men and

women alike it first betrayed itself by the emergence of certain tumours in the

groin or armpits, some of which grew as large as a common apple, others as an

egg...From the two said parts of the body this deadly gavocciolo soon began to

propagate and spread itself in all directions indifferently; after which the

form of the malady began to change, black spots or livid making their

appearance in many cases on the arm or the thigh or elsewhere, now few and

large, now minute and numerous. As the gavocciolo had been and still was an

infallible token of approaching death, such also were these spots on whomsoever

they showed themselves."

Ziegler comments

that the only medical detail that is questionable is the infallibility of

approaching death, as if the bubo discharges, recovery is possible.

This was followed

by acute fever and vomiting of blood. Most victims died two to seven days after

initial infection. David Herlihy identifies another potential sign of the

plague: freckle-like spots and rashes which could be the result of flea-bites.

This was followed

by acute fever and vomiting of blood. Most victims died two to seven days after

initial infection. David Herlihy identifies another potential sign of the

plague: freckle-like spots and rashes which could be the result of flea-bites.

Some accounts,

like that of Louis Heyligen, a musician in Avignon who died of the plague in

1348, noted a distinct form of the disease which infected the lungs and led to

respiratory problems and which is identified with pneumonic plague.

"It is said

that the plague takes three forms. In the first people suffer an infection of

the lungs, which leads to breathing difficulties. Whoever has this corruption

or contamination to any extent cannot escape but will die within two days.

Another form...in which boils erupt under the armpits,...a third form in which

people of both sexes are attacked in the groin

Causes

Medical knowledge

had stagnated during the Middle Ages. The most authoritative account at the

time came from the medical faculty in Paris in a

report to the king of France

The importance of

hygiene was recognized only in the nineteenth century; until then it was common

that the streets were filthy, with live animals of all sorts around and human

parasites abounding. A transmissible disease will spread easily in such

conditions. One development as a result of the Black Death was the

establishment of the idea of quarantine in Dubrovnik

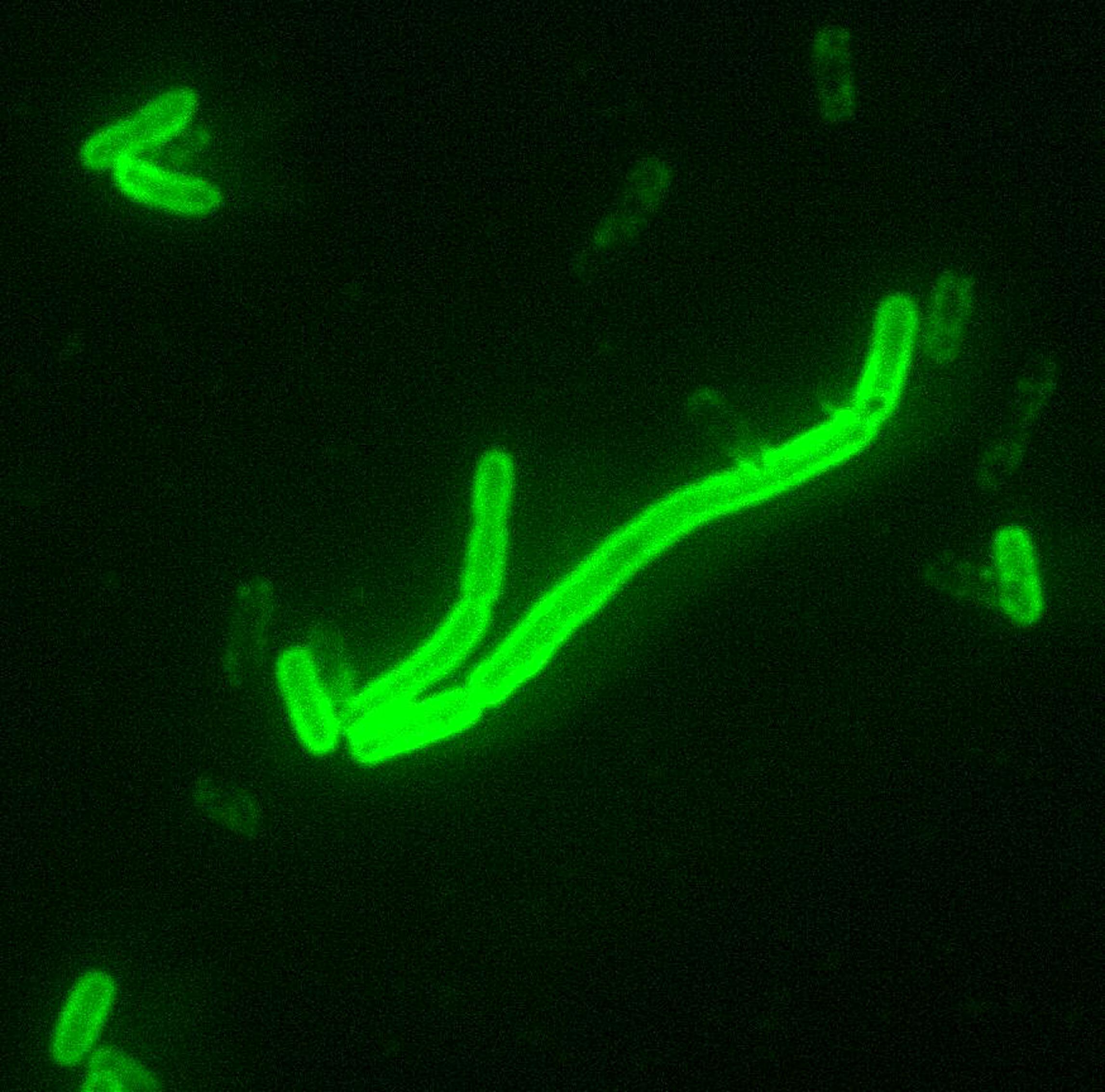

The dominant

explanation for the Black Death is the plague theory, which attributes the

outbreak to Yersinia pestis,

also responsible for an epidemic that began in southern

The dominant

explanation for the Black Death is the plague theory, which attributes the

outbreak to Yersinia pestis,

also responsible for an epidemic that began in southern

The historian

Francis Aidan Gasquet, who had written about the 'Great Pestilence' in 1893 and

suggested that "it would appear to be some form of the ordinary Eastern or

bubonic plague" was able to adopt the epidemiology of the bubonic plague

for the Black Death for the second edition in 1908, implicating rats and fleas

in the process, and his interpretation was widely accepted for other ancient

and medieval epidemics, such as the Justinian plague that was prevalent in the

Eastern Roman Empire from 541 to 700 AD.

More recently

other forms of plague have been implicated. The modern bubonic plague has a

mortality rate of 30 to 75 percent and symptoms including fever of 38–41 °C

(101–105 °F), headaches, painful, aching joints, nausea and vomiting, and a

general feeling of malaise. If untreated, of those that contract the bubonic

plague, 80 percent die within eight days. Pneumonic plague has mortality rate

of 90 to 95 percent. Symptoms include fever, cough, and blood-tinged sputum. As

the disease progresses, sputum becomes free flowing and bright red. Septicemic

plague is the least common of the three forms, with a mortality rate close to

100 percent. Symptoms are high fevers and purple skin patches (purpura due to

disseminated intravascular coagulation). In cases of pneumonic and particularly

septicemic plague the progress of the disease is so rapid that there would

often be no time for the development of the enlarged lymph nodes that were

noted as buboes.

"Many modern scholars accept that the lethality of the Black Death

stemmed from the combination of bubonic and pneumonic plague with other

diseases and warn that every historical mention of 'pest' was not necessarily

bubonic plague...In her study of 15th-century outbreaks, Ann Carmichael states

that worms, the pox, fevers and dysentery clearly accompanied bubonic plague

No comments:

Post a Comment